"Sold on Murder: The life and death of a rebel without a cause" by Howard Altman. April 2, 1990. <--- Hyperlinked to full published article.

"What makes the investigation so difficult, says Butler, is the fact that John Robinson was one of the best-known people in New Haven."

"... police sources are convinced that Robinson knew who murdered him."

SOLD ON MURDER:

The life and death of a

rebel without a cause

New Haven Advocate (CT)

by Howard Altman

April 2, 1990

They sat on the grass in twos and threes, crying and commiserating, remembering a lost friend.

In suits and neckties, jeans and tie-dyes, they came to the master's house of Davenport College to pay last respects to the man they called "Rokked" - a 24-year-old musician named John Evers Robinson, who on March 12 was murdered in the Temple Street office he was renting to practice his music and hone his dreams.

To date, the identity of his killer or killers is shrouded in mystery. The word on the streets is that Robinson, reputed to be a small-time pot seller, may have been putting together a few thousand dollars to make one final drug score (possibly involving cocaine) that would get him out of debt and pay for the production of a record. Robinson's friends say one of the most important things in his life was his band -- Sold On Murder -- and the songs he wrote and performed.

His friends are putting together a fund to product the album.

Another theory is that Robinson was attacked by Nazi skinheads, possibly for racial motives, possibly to settle an old score involving a stolen cymbal.

Either way, police sources are convinced that Robinson knew who murdered him. There was no sign of forced entry at the studio and a set of keys to the rehearsal space was found at the scene.

Though New Haven Police are refusing to narrow down the motives in their investigation, one thing is certain. New Haven has lost, in the words of Chief Administrative Officer Douglas Rae - with whom Robinson lived for about a year - "the city's universal citizen."

Sonny Boy Williamson crooning the blues blasted out of an upstairs window as mourners, mostly in their teens and early 20s, sat outside drinking beers, puffing cigarettes, wondering how something like this could happen to someone so young and wondering too who could take away such a promising life.

Inside, Robinson's parents Jerry Robinson and Frances Jackson discussed the tragic irony of their son's murder.

Robinson and Jackson had each devoted a large portion of their adult lives working to help kids in trouble. As assistant director of the Massachusetts Department of Social Services (DSS), Jerry Robinson is responsible for keeping children out of harm and investigating the increasing instances when that is simply not possible. Frances Jackson manages a youth service program in Kansas "to help find ways for kids to cope who are on the verge of dropping out of school."

John Robinson's murder was exactly the type of thing his parents worked so hard to prevent happening to other children, But now, with John a victim of a wave of violence that is killing off the children nation-epidemic of kids dying. There is an increase in the daily violence and increasingly, children are becoming the victims. Ironically, "this has hit home."

"I wanted," said Frances Jackson, "to make John my own special project. I told him I was thinking of stopping my work [with troubled youth in Kansas] and making him my special project. But he told me not to consider it, that education is too important and that the kids here need me."

Though Frances Jackson said she never wanted her son to come to New Haven, she also knew there was nothing to do to stop him. Once John Robinson got an idea into his head, say those who knew him, there was no stopping him.

John Robinson left his mother's home in Kansas in 1980 at the age of 14 to move in with his father, who had come to New Haven as a graduate student at the Yale University School of Public Health. According to one friend, John's mother called his father hours before John was to fly from Kansas to New Haven and said they would have to talk about John moving east. John's father, the friend said, told John's mother that it was an issue the two would have to discuss in near future. John's mother then said the future was at hand, and that John's father had a choice. Either pick him up at the airport in a few hours ow wait for John to hitchhike across country.

It would not be long before John Robinson became a fixture in town - a fixture say his many friends and acquaintances, they still see in every corner of New Haven. Robinson, according to those who knew him, had a way of disarming strangers and making them his friends.

"When John first came here to stay with me," said his father at the memorial service, "he knew everyone in the university housing unit where we were living by the end of his first week there."

A gifted child, Robinson applied for and was accepted to Hamden Hall Country Day School a private school in Hamden. It was here that he met Rae, they the school's soccer coach. Observing Robinson playing soccer, says Rae, offered a good insight into who John was and what made him tick. Rae's observations dovetail nicely with who John's friends say what the real John Robinson.

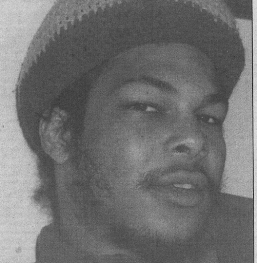

[Photo black & white: caption : Victim Robinson: 'The city's universal citizen.']

Though one of the biggest boys on the team and a natural leader, Rae says Robinson was hardly a great player. Like many other areas in his life, Robinson could not conform with the structure required to succeed in team sports.

"John was a radical," says Rae. "He was a kid who did the difficult [things] brilliantly and the easy things not at all or badly. He was a very bright kid, but his common-sense judgment was a little shaky.

Robinson, says Rae, had no shortages of opinions and was able to defend his thoughts as well as anybody. "He was one of the hardest guys in town to win an argument from." says Rae.

Hamden Hall, he adds, was the perfect educational setting for someone like John Robinson.

"He was a kid who took the message of a progressive education at face value," says Rae. "He questioned every assumption, tried out either variant or eventuality and attacked every evil in a way that took us at our word. The best and worse features of his life reflected that."

As a child in Kansas, says his mother, John's relatives used to call him "the Senator" for his ability to make a point. His great-grandmother called him the "Golden Boy" for his talent and creativity. He wanted to be a lawyer or a surgeon. He won a singing contest at school when he was 10 and he wrote poetry. He has a fascination for science that led to a fascination for art. One science project, dealing with ecology and pollution, turned into an art project. Collecting junk from roadside ditches to illustrate how humans have trashed the environment. John saved his findings and turned them into sculpture.

But, like Doug Rae, Frances Jackson says what made John special eventually worked against him.

"One of the horrible things when you have this type of personality," says Jackson, "is that they take care of everyone else's needs and not take care of their own."

In 1983, when Robinson's father moved to Boston to take the DSS job, Rae asked John to move in so he could finish his schooling. "We took in a few kids over the years, " says Rae.

One thing Rae noticed about Robinson was the young man's living habits. "He was an incredible slob," says Rae with a grimace. "He was in many ways gifted intellectually, but he was also very unworldly and naive."

Though Rae was less than impressed by Robinson's bass playing, he was amazed at the wide circle of people John called his friends. From Yale professors to street people, Rae says Robinson was able to reach out to people from different lifestyles that would otherwise pass each other in the street without even exchanging hellos.

Robinson's wide circle of friends included Yale students, to whom he hung out with, played music for and sold pot to, and the punks, skinheads, street people and scene-makers who hung out on Broadway.

Through firmly ensconced as New Haven's unofficial universal citizen, John Robinsons, say some of his friends, wanted out of the scene. By the summer of 1989, says Sol Fussiner, a close friend, Robinson started thinking about moving out of New Haven.

"He was thinking about moving away from New Haven with the band," says Fussiner. "He wanted to do something with the band, but was frustrated because the people in the band were too attached to New Haven. He thought they should break with all those attachments and move on."

Robinson never did make it out. Doug Rae says he suspected John was getting involved with the wrong people, but never really showed signs, at least while living with the Raes, of wandering over the edge Robinson prided himself on pushing forward. Robinson's friends say he was acting "a little strange" in the last months of his life but, because he kept his personal thoughts and concerns so close to his vest, nobody knew exactly what was going on.

"The last time I talked to him," says Francis Jackson, "was about a week and a half before he was murdered. He was talking about going back to school, about changing his life. He was interested in all the legislation that would have to be written with all the barriers coming down all over the world. Then he started talking about his music. I knew he was in transition."

Rae says Robinson lived for a while with Rae's mother, then in an apartment, then with a succession of friends and acquaintances. His life became nomadic at best. And Robinson, say his friends, left behind a string of debts and, in some cases, hard feelings.

One friend, who used to be closer but grew distance because Robinson owed him money, says that despite all the problems, he still loved John.

"That's the part about this that really sucks," says the friend. "I really miss him."

John Nutcher, Sold on Murder's drummer and one of Robinson's closest friends, says he hardly heard from or saw John in the weeks leading to his death. "I usually talked to him every day," says Nutcher, "but in the weeks before his death, he was acting a little strange. I almost never heard from him."

The band, says Nutcher, was in the process of recording and mixing 14 or 15 songs for an album. John composed the music for most of the songs and wrote about half the lyrics. Robinson, says Nutcher, wrote about personal politics and relationships. Typical of the theme of Robinson's music is a piece called "Divest," a reggae-and ska-influenced song dealing with apartheid in South Africa.

"John was a very opinionated person," says Nutcher. "He was very articulate, very intelligent and was determined to be around a lot of people. His songs reflect that."

Band members, says Nutcher, were trying to get a loan of three or four thousand dollars to finish the album and where [sic] getting ready for a gig at New York City's famous punk club, CBGB, when they found the news about Robinson being found dead in the rehearsal space.

"My first reaction was that the skinheads did it," Nutcher says. "They were outraged at him because they believed he had something to do with a cymbal stolen from a skinhead band called Skeletal Ambitions. But there was no proof that John had anything to do with it."

Nutcher says he thinks it unlikely that Robinson was killed by skinheads, either for racial motives or as revenge for the allegedly stolen band equipment. More likely, he says. are the rumors that Robinson was killed in a robbery attempt because he was carrying a large amount of money to be used to buy drugs to pay for the album.

According to New Haven police Commander J. Thomas Butler, head of the department's detective unit, police are not ruling out any scenarios. What makes the investigation so difficult, says Butler, is the fact that John Robinson was one of the best-known people in New Haven.

"This is the type of case," says Butler, "Where the victim's lifestyle was so expansive that the investigation has to be just as expansive."

So far, says Butler, detectives have interviewed nearly 100 people. They have been assisted by Yale officials, city administrators and the Broadway-area business community, all of whom had contact with John Robinson and his friends and acquaintances.

"He knew more people that I do." says Butler. "This is the most expansive case I have observed in my six months in charge of detectives, and one of the most expansive cases in recent memory."

While he feels strongly that the killer or killers are still in New Haven and that he is "comfortable" with the progress of the investigation, Butler has nevertheless asked for outside help in the form of reward money from the state. It is now up to Gov. William O' Neill, says Butler, to offer a reward for information leading to the conviction of whoever killed Robinson.

Police can trace Robinson alive until around noon March 12. While Butler refuses to discuss potential motives or specifics of the crime he did tell the Advocate that one skinhead, whom sources say goes by the name of Nathan, turned over to police a blunt instrument, said to be a sawed-off baseball bat, for analysis. Butler also revealed that though robber is considered as a potential motive, a "small amount" of money was found on Robinson by officers investigating the murder scene, an "unkempt, two-room office/studio at 178 Temple Street leased to John."

Though investigators discovered many fingerprints, the large number of people who knew John makes it difficult for police to narrow down the prints to possible suspects. "John knew so many people." says Butler, "it is hard to say who should have been and should not have been in the room."

Butler says the investigation is considered a "high priority" by police and that the department is confident that the murder mystery will be solved.

No matter who killed John Robinson, or why, New Haven, say many of his friends, will never be the same place.

"I am thinking about getting out of here," says Danielle Kane, who met Robinson six years ago when she was 15. "New Haven will never be what it was when John was alive. I think a lot of his friends are thinking about getting out of here."

(One way friends and band members are trying to cope with the tragedy of Robinson's death is by raising money to finish the album. A fund has been established and donations can be sent , payable to SOM Records, P.O. Box 1496, New Haven, CT 06506.)

Though he had many troubles in his life and he often brought heartache and pain to those who knew and loved him, John Robinson was a comfort and a strength and someone who marched to his own drummer.

"The extent of waste, of lost possibilities," says Doug Rae, "is nearly record-breaking, and certainly heartbreaking."